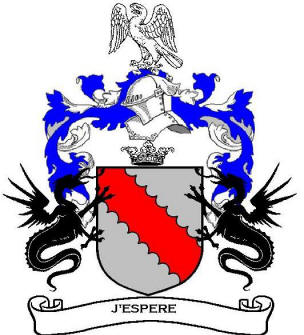

The Culpeper/Colepeper Coat of Arms

The Coat of Arms of John Lord Colepeper

(Culpeper) of Thoresway. Note that this falcon, unlike

some versions, has

its wings inverted. Note also, the motto, "J'espère".

The supporters are two dragons, ducally gorged, which means, not

that they have their bellies full of dukes, but that they have

ducal coronets around their necks. Only peers are entitled to

supporters, and in their case, the helm faces towards the front,

whereas in all those below the rank of baron, it is seen from the

side. The helm rests on a baron's coronet. (Source: Glen N.

Colepeper of South Africa)

|

This color rendering was provided to Culpepper Connections! by

James Thomas Culpepper of Memphis, TN. |

Introduction

A complete Coat of Arms consists of a shield, crest and motto (if one exists). The

shield, or escutcheon, is the main element. The crest is usually an animal and rests on

top of the shield. The motto may be in any language, but is usually in Latin, French or

English.

Note that while many people may refer to a coat of arms as a "crest", the

crest is only one element of the coat.

Where Coats of Arms have existed, they have always been associated with a

specific family and the right to display the Coat passed from generation to

generation through the male line. Thus, there has never been a single Coat of

Arms that could be said to belong to all with a given surname.

However, in connection with the historical Colepepers and Culpepers of

England, one specific Coat of Arms has generally been connected with the family.

While no modern day Culpepper could be said to have the "right" to

display this Coat, many have adopted it as if it were theirs, and the remainder

of this discourse will deal with that Coat of Arms.

The Culpeper Blazon

The description of a Coat of Arms is known as its "blazon." The

Culpeper blazon [with abbreviations spelled out] from Burke's General Amory1 is:

Argent, a bend engrailed, gules

Some background material will help explain the meaning of this cryptic blazon. First,

from Britannica On-Line2:

Coat of Arms, also called Shield of Arms, heraldic device dating back to 12th-century

Europe, used primarily to establish identity in battle but evolving to denote family

descent, adoption, alliance, property ownership, or profession--the oldest extant document

being a copy of a roll of arms of the king of England from about 1240. The coat of arms

consists of a shield, or escutcheon, and surface, or field. It is divided into nine parts

(called points) in order to properly position bearings. It is further divided into chief

and base, or top and bottom, and it is often ornamented with helmet, mantling, wreath,

crest, badge, motto, supporters, crown, or coronet. The left, or sinister, side is to the

observer's right; the right, or dexter, side to the left; and the entire display is

designated the achievement. At first simply assumed, the coat of arms was later given

under royal grant, the College of Arms being established in London in 1484 by England's

King Richard III.

Originally the coat of arms was a cloth tunic worn over, or occasionally to conceal,

armour; or, in place of armour, it was padded and worn for protection but marked with the

shield's identical emblem to aid identification. Just as shields themselves were

artistically embellished to record personal or family themes or history, so too were they

chosen as emblems for organizations far removed from war--e.g., schools, universities,

guilds, churches, fraternal societies, and even modern corporations--to reflect their

mottoes or histories. Closely related to the science of heraldry and the study of

genealogy, coat-of-arms design reflects historical tradition, relying on established

patterns, positioning, symbols, and colours....

Continuing, under "heraldry"3,

according to Britannica On-Line:

The principal vehicle for displaying the heraldic devices is the shield. The crest, a

subsidiary device, emerged in the late 14th century; it was modelled onto the helm. In

pictorial representations the shield, on which the arms are borne, is surmounted by helm

and crest; the latter is usually placed within a wreath or coronet, or rests upon a

chapeau (a crimson cap turned up with ermine). The type and position of the helm indicates

the rank of the bearer. In the late 15th century great nobles, and later certain

corporations, were accorded supporters, creatures on either side of their shields to

support them. At the same time insignia were used with arms; the garter of the Order of

the Garter surrounded the shield; peers placed their coronets above their shields; and

later orders and decorations were shown below the shield. The whole display is called an

achievement of arms.

In the design of arms a wide variety of symbols are used, depicted and arranged

according to a series of conventions. Arms are hereditary; all male descendants of the

first person to whom arms were granted or allowed bear the arms. Younger sons add small

symbols, called marks of cadency, to their arms and crests. Arms are insignia of honour

and so are protected by law. Today only the European monarchies, Ireland, Switzerland,

South Africa, and Zimbabwe control the use of arms. In some countries there is non-noble

or burgher heraldry, but this generally enjoys no protection.

Tinctures are hues used in heraldry, which are denoted colours, metals, and furs. The

colours are gules (red), azure (blue), sable (black), vert (green), and

purpure (purple). Rarely used are murrey (sanguine), tenné (an orange-tawny colour), and

bleu celeste (sky blue). The metals are or (gold, often represented by yellow) and argent

(silver, invariably depicted as white). The furs are ermine (black spots on

white) and such variations as erminois (black spots on gold) and vair (small symbolic

squirrel pellets), alternately white and blue.

The symbols used in heraldry are called charges. The principal charges are

ordinaries--geometrical shapes such as the pale (a broad vertical strip), the fess (a

horizontal strip), and the bend (a diagonal strip). [The Culpeper shield is a

bend.] Other charges are animate--beasts, monsters, humans, birds, fish,

reptiles, and insects--or inanimate, which includes almost everything else.

The field, the background of the shield, is "charged" with the charges. It

may be plain, patterned (checkered), semé (strewn with little charges), or divided by a

line or lines following the direction of the ordinaries. A shield divided into halves

vertically is per pale, horizontally, per fess, and diagonally, per bend dexter (from

upper right) or per bend sinister (from upper left). The dividing lines may be embattled

(crenellated), wavy, or indented (zigzag). [Another pattern for the dividing

lines is "engrailed", which means indented with small concave curves.4 This

is the style used in the Culpeper shield.] The top area of the field is the

chief and the bottom the base. The shield is viewed as if being borne, so the viewer's

left is the right, or dexter, and the viewer's right, the sinister. The top centre is the

honour point, the middle centre the fess point, and the base centre the nombril point.

To describe an achievement is to blazon it. The terms of blazon are in general a

mixture of English and old French. Blazon is based in conventions that make it terse and

unequivocal. Charges always face dexter, for example, and three charges on a shield are

placed two in chief and one in base unless otherwise blazoned. There are many such

conventions. The basic rules of blazon are to describe, in this order, the field, the

principal charge (often an ordinary), other charges, and charges on charges. Adjectives

follow the nouns they qualify, the tincture coming last; a red rampant lion on a gold

shield is blazoned "Or a lion rampant gules."

From the foregoing. the Culpeper blazon, "Argent, a bend engrailed, gules"

may now be translated as

A silver shield with a diagonal red stripe indented with small concave curves.

Above the shield and a helmet is the crest, which is described in Burke's5 as:

A silver falcon with extended wings whose beak and bells are gold.

Another source, an old pedigree chart for the Colepepers of Bedgebury,

describes a

crest that is more elaborate:

On a trunk of a tree, lying fessways, a branch issuant from the dexter end, proper,

a falcon, wings expanded, argent, beaked, belled and legged, or.

To define 4 some of the more obscure terms: fess:

a broad horizontal bar across the middle of a heraldic field; dexter: to

the right of the person bearing it; proper: represented heridically in

natural color; argent: silver or white; or.: gold.

The Motto

"In England, mottos do not form part of the patent and can vary

within families, within generations of the same families, etc. Usage

varied from next to none early on, to primarily in French during the

Tudor Era, to mainly in Latin by the 16th Century. The more they were

used, the more the appeared in the actual paperwork on grants of

arms." (Source: Bill Russell)

We have been able to identify three different mottos that have

appeared with the Culpeper Coat of Arms:

-

J'espère

-

Jesu Christe fili Dei miserere mei

-

Fides fortitudio fastio

1. J'espère

Glen Colepeper, a university professor in South Africa, reports that the motto of

his ancestors, the Barbados

Culpepers, as well as that of John, Lord Culpeper, was the French:

J'espère.

Translation: I hope.

Glen also called our attention to a reference to the

Culpeper Coat of

Arms in Michael Drayton's The Barons Warres, Canto 2, Verse 23? It

reads as follows:

And Culpeper, in Silver Arms enrayl'd

Bare thereupon a bloudie Bend engrayl'd

("Enrayl'd" means "enclosed".)

2. Jesu Christe fili Dei miserere mei

On a pedigree chart for the Colepepers of Bedgebury,

there was the following notation

about the colors of the shield and the motto:

As I have hearde my ffather Sr

Allexr Colepeper saye thatt Rede and White are

the cullers of us the Colepepers of Bedgebury, and thatt owr

worde is "Jesu Christe fili Dei miserere mei."

Teste Antho: Colepepyr

Translation: Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy

upon me.

However, as Glen Colepeper points out, this is rather

long for a normal motto, so its authenticity is in doubt.

3. Fides fortitudio fastio

One motto that has appeared with the Coat of Arms contained a Latin-sounding

motto:

Fides fortitudio fastio. It's origin is uncertain; we found it on the photograph of a needlepointed version of the Coat.

Dr. Sarah Culpepper Stroup obtained her Ph. D. in Classics

(Greek and Latin) from the University of California at Berkeley in 2000

and is now a Professor of Classics at the University of Washington in

Seattle. A few years ago (late 1998) she was kind enough to offer a suggested translation and explanation.

As the reader will see, Sarah had to strain to translate

it. Given her expertise in Latin and the lack of any evidence for the

motto older than our photograph, Warren Culpepper and Glen Colepeper both

believe that this is probably not the authentic motto of one who was

entitled to the Coat.

Sarah's translation:

Fides fortitudio fastio = Faith, Courage, Dignity

|

Fides

Fides = 'faith'. No question here.

|

|

Fortitudio

This isn't a Latin word, but perhaps what it says (or means to say)

is 'Fortitudo,' which would be just fine, and means 'bravery' or

'courage' (it can also mean brute physical strength, but I'm favoring

a more poetic translation).

|

|

Fastio

'Fastio' is not found in classical Latin (which I study). It

appears neither in the Latin vulgate nor in any medieval Latin

lexicon. This means that either:

|

-

The word appears only in very late Latin, when all sorts of

strange things start happening to the language, or

-

The word was invented by someone who maybe knew a little Latin and

wanted another noun that begins with 'f'. (Mottos like assonance:

the motto of the clan Stewart is virtus vulnere virescit:

"excellence grows verdant from the wound").

In either case, I think that the word must mean (or, was intended to

mean) something like 'pride' or 'dignity.' In classical and medieval

Latin the word 'fastus' appears, and it means something like 'haughty

contempt' or 'arrogance'--in general, it has negative connotations, but

may occasionally mean something like 'pride' in a relatively positive

sense. The -io ending for a noun is perfectly valid, but occurs only

with nouns that are formed from *verbs* (for instance, 'actio' "an

action" comes from the verb 'agere, actus' = "to do"; but

fastus / fastio cannot be thus formed: there is no verb from which they

would come).

What is possible, I think, is that the formation of 'fastio' was an

attempt to create a positive or favorable term for 'pride' or 'dignity,'

which begins with an 'f,' and is therefore a neologism formed from 'fastus'

(just as 'actio' comes from 'actus'; except that 'actus' "having

done" is a participle, whereas 'fastus' is a noun). Grammatically

and orthographically, this formation is totally bogus; it is like using

the ending of the word 'Marathon,' which is actually a place name, and

applying it to any extended activity: dance-athon, bike-athon, eat-athon,

etc. These words don't really 'mean' anything, but they are perfectly

understandable, because anyone for whom English is the primary language

can figure out the connection. Ditto with Latin, and especially late

Latin, when the rules become very flexible.

Charles Edward Culpepper, III wrote on 14 Sep 2013 this commentary on

Fides, Fortitudio, Fastio

Looking at

translation considerations of Glen, Sarah and you; and taking into

account my expertise on Martial Arts. I believe that the translation

runs into the issue of connotation versus denotation; more to the point,

it is not a Latin translation problem, but more a cultural history

problem.

I think that

you could interpret Fides, Fortitudio, Fastio loosely as: Faith,

Fortitude, Pride or Dignity. But I believe the author intended it to

mean: Faith, Duty, Honor. Has a ring to it, no? Almost sounds like a

modern marine motto. Or something the character 'Dawson' would have said

in the movie, A Few Good Men - along with: "Unit, Corp, God, Country".

Some

background. In all warrior faiths, there is great need to distinguish

between dying via 'daring and bearing' as opposed to dying to escape

fear or pain. Even a cursory knowledge of classic interpretations of the

four cardinal virtues, i.e., prudence, courage, justice and temperance

makes you realize how these words have a different meaning to the modern

ear.

In the classic

world prudence is the ability to distinguish between what is 'right' and

'wrong' and by right and wrong is meant, good or bad for the society.

Prudence is to know what is right. Courage, or fortitude,

is the act of not shirking the responsibility to do what is

right, when you know what is right, regardless the personal sacrifice.

Justice means doing right for the sake of doing right, rather

than for personal interest or gain, what we today would call altruistic.

The best interpretation of temperance would be proportional

response. It is not anything like our present goofy interpretations as

chastity, abstinence or the like. Our individualistic version of society

is nothing like classic or ancient society. They would no doubt find us

immoral, unworthy, dishonorable and stupid...

For, what I

believe to be obvious reasons, warriors, their commanders and sovereigns

all regard the most important part of a warrior/knight/soldier code to

be fortitude, in the form of perseverance and resolve. And this

begs the question 'what's in it for the fighter'. The answer is of

course honor. Honor is not expensive for commander or sovereign

to provide. Men of action covet honor precisely because it demands so

much. It distinguishes them as men of daring and bearing who can be

relied on. Best exemplified in the Spartans of ancient Greece who

accepted poverty and a life devoid of comfort. Spartans valued only an

honorable life and death.

You might want

to read this passage from Bushido, the Soul of Japan, by Inazo

Nitobe (1905)

http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/bsd/bsd09.htm . It is probably the

best book every written on Bushido or Chivalry. It is a wonderful read,

even if you have no particular interest in the subject. It liberates and

enlightens the mind in a provocative and splendid way.

If you are aware of other mottos that have appeared with the

Culpeper Coat of Arms, please contact

us.

The Culpeper Coat of Arms6

By Col. F. W. T. Attree

The armorial bearings of the family, Arg: a bend engrailed, gu., may possibly

furnish a clue to its origin. Papworth, in his Ordinary of British Armorials, mentions

some sixty families as bearing the bend engrailed, but apparently only two of them, viz.,

Chitcroft and Walrand, displayed identically the same coat as the Colepepers.

As Robert Walrand, in the Roll of Arms, temp. Henry III., appears as the owner of this

coat, the Colepepers probably got it somehow through him, and they were using it as early

as 3 Edward III. (1329), when John, the son of Sir Thomas Colepeper, is recorded as

bearing it, and his brother Richard differenced it with a label of three points.

The Chitcrofts also were probably either Colepepers or closely connected with them, as

not only are their arms identical, but we find the two families associated together at a

very early period. In 1299 Benedicta, daughter of Thomas de Chitcroft, granted land in

Beghal, with a mill in Pepinbury, to Thomas, son of Thomas Colepeper, and Margery his

wife, while in ll Henry IV (1409) the names of John Chitcroft and Thomas Colepeper

chivaler, appear coupled as defendants in an action brought by John Mortymer, relating to

the manor of Asshen, co. Northants.

An investigation of the early Walrand and Chitcroft pedigrees would doubtless reveal

some connection with Colepeper, but would probably give no clue to the origin of the name,

which may, therefore, be left to the choice of the reader or to his further researches.

1 John

Burke and John Bernard Burke: General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales.

London: Harrison and Sons, 1884.

2 "arms,

coat of" Britannica Online.

[Accessed 04 September 1998].

3

"heraldry" Britannica Online.

[Accessed 04 September 1998].

4 Webster's

Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary, Merriam-Webster Inc, Springfield, MA, 1983.

5 Burke. Ibid.

6 Colonel F. W. T. Attree, R.E., F.S.A., and

The Rev. J. H. L. Booker, M.A, "The Sussex Colepepers",

from Sussex Archaeological Collections,

Vol. XLVII, 1904.

Last Revised:

02 Jan 2015

|