Catherine Howard

Part III of III

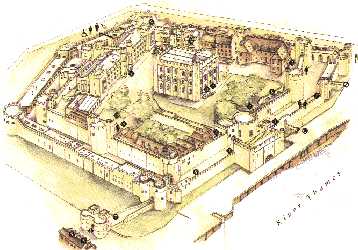

Map of the Tower of London

Chapter IX

The story, so far, was one of Manox and Derham. When Wriothesley came from the Tower to

the council, to piece Cranmer's document with his own, there could be no shadow of doubt

that Lassells' sister had been absolutely justified. Derham had confessed that he had

known Catherine as she had described.

The King had chosen his young bride for personal reasons. He heard this revelation not

as a man of power, in whom the passion of power and the apprehensiveness of power were

uppermost. He heard it as a very simple human being.

A deep silence came on the council as the disclosure of Catherine's blemish was made, a

blemish that could never be hidden and that secretly pleased every one who had seen a

target in her temperament.

It was a long time before Henry could utter his sorrow. He sat there, feeling old, his

heart "pierced with pensiveness." Then he began to cry. It must have moved every

one. "And finally, with plenty of tears, which was strange in his courage," he

opened the heart that had been wounded.

Chapter X

This was the indulgent Henry that Catherine had known. And had she been behaving

properly during her marriage, she might have escaped being sent to a nunnery for life. But

the past treads on the present. Lassells' sister had cited the chamberer Tilney at the

Duchess's. Tilney was hunted up and she mentioned Marget Morton: Morton named Culpeper.

"I never mistrusted the Queen," exclaimed this woman, "until at Hatfield

I saw her look out of her chamber window on Master Culpeper after such sort that I thought

there was love between them."

This was the thing Catherine had feared. Before she could warn Culpeper to save

himself, he was caught and sent to the Tower.

As the council reported the scandal in a graphic letter November 11th, to Paget at

Paris, they wound up significantly, "Now you may see what was done before marriage.

God knoweth what hath been done since."

Chapter XI

Norfolk's thin lips curled bitterly. He first told Marillac that his niece had

"prostituted herself to seven or eight persons." This was out of his

imagination. Later he said that only Derham was clearly proved. He told Marillac of

Catherine's state. She "refuses to drink or eat and weeps and cries like a madwoman,

so that they must take away things by which she might hasten her death."

Her uncle felt no pity for her but the deepest pity for Henry. He spoke with tears in

his eyes of the King's grief, who loved her much, and of the misfortune to his own house

in her and Anne Boleyn. Henry was so grieved, he said, that he proposed never to take

another wife.

But even the Culpeper disclosure did not turn Henry against Catherine. He did not see

her again, but his heart was not hard. He bowed to the catastrophe and Chapuys learned

about this time, November 19th, from sober Southampton that Henry "would show more

patience and mercy than many might think - more even than her own relations wished,

meaning Norfolk, who said, God knows why, that he wished the Queen was burned.'' She was,

however, sent from Hampton Court to be shut up in Syon, "a late nunnery near

Richmond," guarded by four women and some men. And Henry was to go for five or six

days to the country "to relieve his mind."

Chapuys, whose asperity had not been softened by years and who incidentally suggested

to Charles that when Anne of Cleves had a drop taken she was not so different from

Catherine, admitted Henry's grief. "This King has wonderfully felt the case of the

Queen, his wife," the old sinner said, "and has certainly shown greater sorrows

at her loss than at the faults, loss, or divorce of his preceding wives. It is like the

case of the woman who cried more bitterly at the loss of her tenth husband than at the

deaths of all the others together, though they had all been good men, but it was because

she had never buried one of them before without being sure of the next; and as yet this

King has formed neither a plan nor a preference."

Chapter XII

With the two young men in the Tower and Catherine at Syon, there was no chance for her

to warn Culpeper. The ministers continued their invaluable police work. The girl's past

had been scavenged in every "foul detail," as Marillac put it, and it did not

lose in official narration. A dozen servants had been examined. The Lord Privy Seal was

told to "pick out from Wilkes" anything that might trip up Lord William Howard.

Wriothesley wrote with zest to Sadler, "My woman Tilney hath done us good

service." And he triumphantly learned that Derham had once said, "An the King

were dead I am sure I might marry her." This was volunteered by another youth.

"And no torture," exclaimed the minister, "could make him confess this

before."

The extraordinary eagerness to hunt down every bit of evidence was due to the fearful

and exciting possibilities of treason and conspiracy. The old Duchess of Norfolk had not

only hidden her moneybags, fearing Henry's avidity, but had broken into Derham's coffers

and destroyed ballads and letters. This raised the ogre: she, her son, her daughter, and

nine servants were quickly rounded up. The divided council were watching Henry as two

sides watched a football and they intended to be thorough.

Derham and Culpeper went to trial on December 1st, before a special commission at

Guildhall. Catherine's young brothers and Culpeper's relations thought it better to show

their indifference by riding about London, while Norfolk, one of the judges, took it on

himself, during the trial, to laugh and jeer. Catherine's signed deposition was read,

pleas of "Not guilty" were soon changed to "Guilty." The story had no

new aspect. Derham admitted complete intimacy, justifying it as an engagement. He was

sentenced to death at Tyburn, to be hanged, cut down alive, split open, his bowels burnt,

and finally killed by beheading. This terrific sentence was also passed on Culpeper.

"Gentlemen," he had pleaded, "do not seek to know more than that the

King deprived me of the thing I love best in the world, and, though you may hang me for

it, she loves me as well as I love her, though up to this hour no wrong has ever passed

between us. Before the King married her, I thought to make her my wife; and when I saw her

lost to me, I was like to die, as you all know how ill I was. The Queen saw my sorrow and

showed me favor, and when I saw it, tempted by the devil, I dared one day while dancing to

give her a letter, and received a reply from her in two days, telling me she would find a

way to comply with my wish. I know nothing more, my lords, on my honor as a

gentleman."

Norfolk's sneer showed how he felt.

"You have said quite enough, Culpeper," Hertford commented, "to lose

your head."

Ten days of renewed cross-examination followed the death sentence; but no further

admissions could be had from them. Derham begged that the extremity of his judgment should

be remitted but "the King thinks he has deserved no such mercy." The council,

however, sent word that Culpeper was "only to lose his head."

On December 10th, the two young men suffered at Tyburn as decreed.

Till the trials were completed Henry was calm, but as the council strummed on his

nerves day by day, each bit of evidence being submitted to him, he suddenly burst out

before them into such a storm of grief and rage, calling for a sword to slay Catherine,

that they gripped their chairs and thought he had gone mad.

"That wicked woman!" he cried, his face tumid with hate and his eyes boiling.

"She never had such delight in her lovers as she shall have torture in her

death!"

These expressions exploded from him in the middle of a conference. All of a sudden he

broke down and began to cry. She was to have been the wife of his old days. His ill-luck

in meeting with such ill-conditioned wives was the thing with which he upbraided his

ministers "I blame my council for this mischief!" In a paroxysm he started up

and called for horses. No one knew where he would go.

But where would he go? England is an island. His council were willing to do anything,

to pass any law, to invent any device, that might protect their master from "the

lightness in a woman" which Francis had just written to deplore. To see him ride away

in this wild fashion alarmed them: they did their best to make him forget his grief. But

he insisted on escaping. "He is gone twenty-five miles from here," reported

Marillac, "with no company but musicians and ministers of pastime."

The master's departure did not mean, however, that he had lost touch with his council.

He had received a bitter lesson from the public when he committed Anne Boleyn to a

criminal death. This time he showed the most masterly comprehension of the art of

preparing public opinion. He himself had superintended every single detail of the case

against Catherine. The young men were tried in full public. Grand juries everywhere that

he and Catherine had been on progress were invited to return true bills. Every minute

direction as to Catherine's detention under Edward Baynton (who had been such a good

bloodhound in the Boleyn case) came from Henry himself, down to her apparel and her decent

style (but "no cloth of estate"). Lady Rochford was set to spy on her, though

herself under condemnation. A most complicated set of questions to be put to the Duchess

of Norfolk was shrewdly revised and pointed by the King. He had his eye, moreover, on her

tangible assets, which were seized and reported to him. But where he had in the earlier

crisis rushed the execution of Anne Boleyn, he was now carefully placing the

responsibility on his tractable parliament. Henry had made costly mistakes and fed

hostility: he had reflected and mastered his lesson.

The council were well trained to carry out his work. In these sparse days of Advent,

they did not fast too arduously. One day and another they had salmon and flounder, sole

and turbot, white herring and bacon herring, gudgeons and pike, shrimps and baked eels and

oysters, beef, mutton, veal "marybones," rabbit, snipe, plover, larks, crane,

quail, geese, peas, beans, onions, cherries, strawberries, pippins, oranges, pears,

chestnuts, pomegranates, and all the other food and drink that go to support the labor of

statesmanship. They were on the whole a team of ample and hearty men. They had little

grudge against the old Duchess and not much against Lord William. They probably rather

enjoyed the fact that the Duke thought it the better part to retreat to Norfolk like a

wary campaigner. The surly willingness of Gardiner to take his share in running Catherine

to ground could scarcely have been lost on any one of them. The extraordinary report that

the King's good sister Anne of Cleves had just made him an uncle, "for the King is

informed that she has indeed had a child and imputes a default in her officers for not

informing him," must have stirred urgent and amused curiosity. The rumor estopped, at

any rate, the English-Cleves-French alliance, and paved the way for that reunion with the

Emperor to which the world was again tending.

But for obvious reasons the council was left dominant. Henry had gone away with his

ministers of pastime. He was once more a man of sorrows. He seemed to turn his back on the

fearful quandary, and to leave Catherine to ministers of state and ministers of grace.

Chapter XIII

She was now cut off at Syon till parliament met in the middle of January. During the

first weeks a feverous madness overwhelmed her, but gradually, with the verve of a girl

under twenty, she recovered her spirits.

She could hope for nothing from the Howards. Norfolk had written to Henry of "the

abominable deeds of his two nieces," fearing "his Majesty will abhor to hear

speak of one of my kin again," but shrewdly reminding Henry of the small love that

his stepmother or his nieces bear him, and praying for a comfortable assurance of that

favor "without which I will never desire to live."

This was an appeal that Henry could grant to the best soldier in his realm. Catherine,

however, was of a new generation. She could ask nothing of Henry. She made no appeal.

"Very cheerful and more plump and pretty than ever." So Chapuys, reported her

at the end of January, saying she was just as careful about her dress, and just as willful

and imperious, as when at court. But her cheerfulness had depths. She expected to be put

to death. She said she deserved it. She only asked that "the execution shall be

secret and not under the eyes of the world."

This acceptance of her fate seemed to arise from her wealth of feeling. She could not

excuse her own insincerity. She had given Culpeper tokens of her love: she had wanted to

give him herself: and, still living in her young imagination, she felt in a sense she was

giving him her life.

For the elders whose imagination had long been paved for the pursuit of power and the

responsibility of the state, the solid men who ate the larks instead of listening to them,

the spontaneity that had ruled Catherine was impossible. She was too young to understand

the complex laws of self-preservation and not old enough to apprehend the dangers of

sincerity. Even Henry, who had cried so much, was returning to social solace, and planning

a huge banquet for young people, with bevies of fresh girls, nearly fifty of them, to

entertain and distract him. Southampton had credited his master with the inclination, so

magnanimous but so intolerably expensive, of indulging his feelings. But, his tears dried,

Henry was employing a cheaper method of soothing his nerves. Catherine had not lived long

enough to master these economies and was even willing to take the consequences of her

dishonesty.

When word came to her that both Lords and Commons had passed the act of attainder and

that the King would allow her to plead before parliament, she did not ask to defend

herself. She submitted entirely to the King's mercy and owned that she deserved death. She

was resigned, or thought herself resigned.

But when Sir John Gage came out I to Syon, a blond-bearded man with mercilessly direct

eyes, to tell her to pack up and make ready for the Tower, an anguish wrung her nerves. At

the actual moment for leaving, as she came to it) her body recoiled, her hands clenched,

she fought back and said, "No, no." But the barges were ready. Engulfed in sobs

she went down to embark at Isleworth. By the time she had reached the Tower, however, her

cheeks in the fever of excitement, she had captured her composure. Southampton was first

in a great barge, with other councilors; Suffolk with his men came last in another great

barge; and she in a small barge with a few ladies and guards. The lords landed first: then

Catherine, in black velvet: "and they paid her as much honor as when she was

reigning."

Gage wits the new governor of the Tower, since William Kingston's death. Lady Rochford

had been out of her mind, off and on, since learning she was to be condemned, but she had

at last come to her senses and was with her mistress. Catherine again broke down in the

Tower, on the afternoon of February tenth. Culpeper had been here before her. "She

weeps, cries, and torments herself miserably without ceasing. To give her leisure to poise

herself and "reflect on the state of her conscience," her execution was deferred

for a few days.

This was on the Friday. On Sunday, towards evening, Gage came to her and told her to

prepare for death, for she was to die next day.

That evening she asked to have the block brought in to her that she might know how to

place herself. This was done, and the young woman made trial of it.

When she came to the block the next morning, February 13th, it was set on the spot

where her cousin Anne Boleyn had been executed. The council, except her old uncle, had

collected in the shiver of the winter morning, with the trees bare, the stars hardly gone

out, and the air wraithed with the nearness of the Thames. A large number of people had

gathered at the scaffold.

She spoke a few breathless words. A Spaniard heard them and wrote them.

"Brothers, by the journey upon which I am bound, I have not wronged the King. But

it is true that long before the King took me, I loved Culpeper, and I wish to God I had

done as he wished me for at the time the King wanted to take me he urged me to say that I

was pledged to him. If I had done as he advised me I should not die this death, nor would

he. I would rather have had him for a husband than be mistress of the world, but sin

blinded me and greed of grandeur; and since mine is the fault, mine also is the suffering,

and my great sorrow is that Culpeper should have had to die through me."

At these words she could go no farther. She turned to the headsman and said,

"Pray hasten with thy office."

He knelt before her and begged her pardon.

She said wildly,

"I die a Queen, but I would rather die the wife of Culpeper. God have mercy on my

soul. Good people, I beg you pray for me."

Falling on her knees she began to pray. Then the headsman severed her bent neck, and

her young blood gushed out in a terrible torrent. Lady Rochford was then brought to the

block, but before she was led out her mistress's little body, covered with a black cloth,

was lifted up and borne to the chapel, where it was buried near Anne Boleyn.

To:

Warren Culpepper

Date: July 28, 2005

Subject: Catherine Howard

I would like to bring to your attentions some interesting information

about the Thomas Culpeper who was allegedly involved in an adulterous

relationship with Catherine Howard, the fifth wife of King Henry VIII.

Firstly, there were two Thomas Culpepers at King Henry VIII's court, and

they were brothers. (It was fairly common for noble families to give their

sons the same name circa the sixteeth century - in this period of high

infant mortality, this was one way of improving the chances that a family

name - in this case, Thomas - would endure). Thomas Culpeper senior was

one of Lord Cromwell's minions, and Thomas Culpeper junior was a Gentleman

of the King's Privy Chamber. It was the latter with whom Catherine Howard

was allegedly involved. As an aside, Lord Cromwell of course was Thomas

Cromwell, the great advisor to King Henry VIII and one of the chief

instigators of the establishment of the Church of England. Cromwell was

charged with heresy amongst other things, and beheaded on the same day in

July 1540 that Catherine Howard and King Henry were married.

There is some documentary evidence that one of the Culpeper brothers raped

a parkkeeper's wife and murdered the man who came to her assistance - it

is fairly difficult to tell which one did commit the crimes but most

historical texts seem to indicate that it was Thomas Culpeper junior who

did it. The King issued a pardon for the crimes, for which the penalty was

usually hanging.

Thomas Culpeper junior was ultimately charged with high treason in late

1541 (for intending to commit adultery with Catherine.) The penalty for

this crime was drawing, hanging, beheading and quartering. However, as

Thomas junior was a favourite of the King, the penalty was reduced to

drawing and beheading.

He was supposedly a man of considerable charm and sex appeal, if not

entirely honourable. The evidence seems to indicate that Catherine Howard

did indeed love him.

Regarding Catherine Howard - it is generally agreed these days that the

words attributed to her - that she would rather die a wife of Culpeper -

she never uttered. Many fables surround Catherine, and that is one of them

- for her to say this at her execution would have been entirely not "the

done thing" . Furthermore the original tale of this arose from a

chronicler who wrote Catherine's "story" a generation after her death, and

whose tale is littered with inconsistencies and inaccuracies. For example,

this chronicler wrote that Lord Cromwell was the one that interrogated her

upon her charge, however as mentioned above, Lord Cromwell was long since

dead.

There are many historical texts that provide this information I have given

to you. Most reputaable texts about King Henry VIII support the

information in general - it it is important to remember about this time

that indisputable information is quite scanty and in fact I often have

often found that accounts differ from one text to another - so I have

tried to give you just the facts that every historian seems to agree on!

In regard to the picture of Catherine - these days it is generally agreed

that the portrait you have on your web site is not Catherine. The author

Antonia Fraser wrote a wonderful study on the matter, drawing this

conclusion. She concluded that the portrait is of Elizabeth Seymour

Cromwell, the sister of Jane Seymour (King Henry's third wife). There is

one other portrait around that historians believe could be Catherine, but

even that is disputable. One has to remember that Catherine was much

maligned after her death and whatever portraits may have existed of her

were hidden away or destroyed by her family.

For what it's worth - and this is just my opinion - I do not believe

Catherine was an adulterer, although she may well have had the wish to be

so (however, having such a wish was high treason, unfortunately, and it

could be 'proved' in all manner of weird and wonderful ways). She would

have been aware of how her cousin, Anne Boleyn, met her death and I am

sure would have been afraid enough not to repeat the same apparent

mistakes. I also am on the fence regarding Thomas Culpeper junior's guilt

of the rape and murder, mainly because his elder brother Thomas was often

getting into violent fights, but there is no record of Thomas junior

having such a reputation. I am leaning towards the crimes having been

committed by Thomas senior. I find Thomas junior to be one of the most

fascinating characters in history, and he was certainly a favourite with

King Henry VIII.

I hope this information is useful to you.

Best regards

Kate

Historian and Lecturer

Last Revised:

02 Jan 2015