Culpeppers in the

War of 1812

The so-called War of 1812 actually spanned several years,

with skirmishes starting as early as 1807 and not ending until 1815. But in

so far as involvement by Culpeppers is concerned, most were

not involved until 1813 when a new theater of operations opened in the south.

The narrative that follows was taken from a much larger work on the

War of 1812,

published by the Center for Military History. We have included descriptions

of only those campaigns that probably involved Culpeppers.

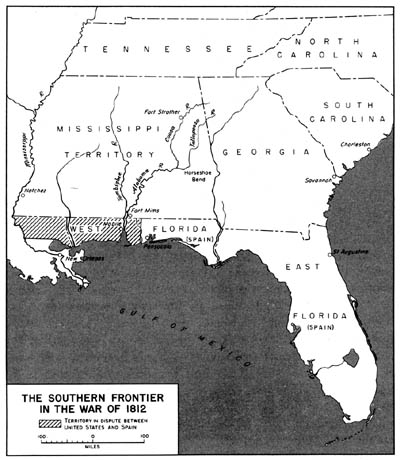

Mississippi Territory (Alabama)

Andrew Jackson, an ardent expansionist and commander of

the Tennessee militia, wrote the Secretary of War that he would "rejoice at

the opportunity of placing the American eagle on the ramparts of Mobile,

Pensacola, and Fort St. Augustine." (Map 17) For this purpose

Tennessee had raised a force of 2,000 men to be under

Jackson's command. Congress, after much debate, approved only an

expedition into that part of the gulf coast in dispute between the United

States and Spain, and refused to entrust the venture to the Tennesseans.

Just before he went north to take part in the Montreal expedition, General

Wilkinson led his Regulars into the disputed part of West Florida and,

without meeting any resistance, occupied Mobile, while the Tennessee army

was left cooling its heels in Natchez.

Map 17

An Indian uprising in that part of the Mississippi

Territory soon to become Alabama saved General Jackson's military career.

Inspired by Tecumseh's earlier successes, the Creek Indians took to the

warpath in the summer of 1813 with a series of outrages culminating in the

massacre of more than 500 men, women, and children at Fort Mims (Baldwin

County, Alabama, north of Mobile). Jackson, with characteristic energy,

reassembled his army, which had been dismissed after Congress rejected its

services for an attack on Florida, and moved into the Mississippi Territory.

His own energy added to his problems, for he completely outran his primitive

supply system and dangerously extended his line of communications. The

hardships of the campaign and one near defeat at the hands of the Indians

destroyed any enthusiasm the militia might have had for continuing in

service. Jackson was compelled to entrench at Fort Strother on the Coosa

River (Calhoun County, Alabama), and remain there for several months

until the arrival of a regiment of the Regular Army gave him the means to

deal with the mutinous militia. At the end of March 1814 he decided that he

had sufficient strength for a decisive blow against the Indians, who had

gathered a force of about 900 warriors and many women and children in a

fortified camp at the Horseshoe Bend of the Tallapoosa River (Tallapoosa

County, Alabama). Jackson had about 2,000 militia and volunteers, nearly 600

Regulars, several hundred friendly Indians, and a few pieces of artillery.

The attack was completely successful. A bayonet charge led by the Regulars

routed the Indians, who were ruthlessly hunted down and all but a hundred or

so of the warriors were killed. "I lament that two or three women and

children were killed by accident," Jackson later reported. The remaining

hostile tribes fled into Spanish territory. As one result of the campaign

Jackson was appointed a major general in the Regular Army.

Presumably, the Culpeppers in the militias of Georgia and Mississippi, and

possibly South Carolina, were involved in these conflicts:

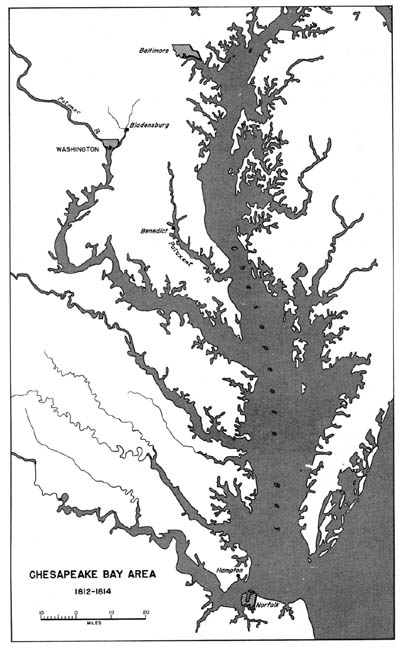

Virginia and Maryland

Fighting also broke out during 1813 along the east coast

where a British fleet blockaded the Delaware and Chesapeake Bays, bottling

up the American frigates Constellation at Norfolk and Adams in

the Potomac. (Map 18) Opposed only by small American gunboats, the

British under Admiral Sir John Warren sought "to chastise the Americans into

submission," and at the same time to relieve the pressure on Prevost's

forces in Canada. With a flotilla, which at times numbered fifteen ships,

Rear Adm. Sir George Cockburn, Warren's second-in-command, roamed the

Chesapeake during the spring of 1813, burning and looting the prosperous

countryside. Reinforced in June by 2,600 Regulars, Warren decided to attack

Norfolk, its navy yard and the anchored Constellation providing the

tempting targets. Norfolk's defenses rested chiefly on Craney Island, which

guarded the narrow channel of the Elizabeth River. The island had a 7-gun

fortification and was manned by 580 Regulars and militia in addition to 150

sailors and marines from the Constellation. The British planned to

land an 800-man force on the mainland and, when low tide permitted, march

onto the island in a flanking movement. As the tide rose, another 500 men

would be rowed across the shoals for a frontal assault. On June 22 the

landing party debarked four miles northwest of the island, but the flanking

move was countered by the highly accurate marksmanship of the

Constellation's gunners and was forced to pull back. The frontal assault

also suffered from well-directed American fire, which sank three barges and

threw the rest into confusion. After taking 81 casualties, the British

sailed off in disorder. The defenders counted no casualties.

Map 18

Frustrated at Norfolk, Warren crossed the Roads to Hampton

where he overwhelmed the 450 militia defenders and pillaged the town. A

portion of the fleet remained in the bay for the rest of the year,

blockading and marauding, but the operation was not an unalloyed success. It

failed to cause a diversion of American troops from the northern border and,

by strengthening popular resentment (Cockburn was vilified throughout the

country), helped unite Americans behind the war effort.

Presumably, the Culpeppers in the militias of Maryland, Virginia and

possibly North Carolina were involved in these conflicts:

New Orleans: The Final Battle

In late 1814 and early 1815, the Battle of New Orleans

occurred. However, less than 4,000 US troops were involved, and it appears

that they probably were not from any Militias that the Culpeppers were in.

Last Revised:

02 Jan 2015 |